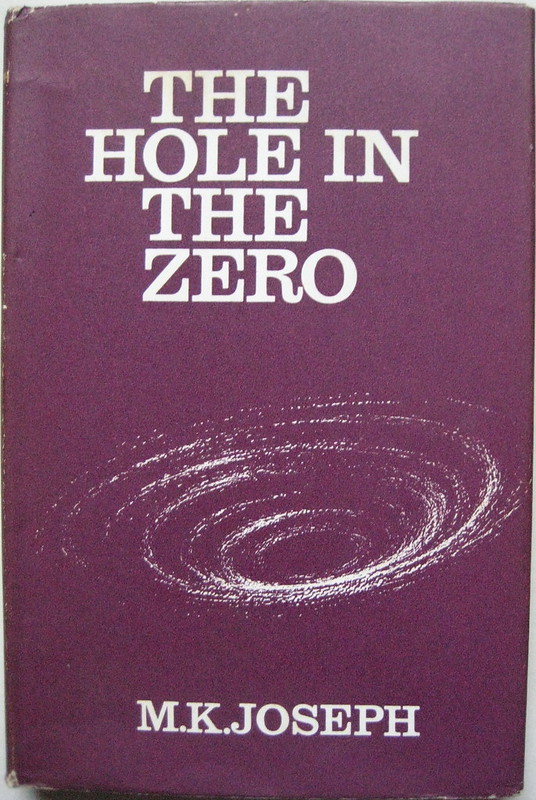

(Ed Soyka’s cover for the 1969 edition)

(Ed Soyka’s cover for the 1969 edition)

3.5/5 (Good)

I love finding a SF book on the used bookstore shelf by an author I have never heard of. I am even more excited when a virtually unknown novel is endorsed by one of the great SF critics, in this case John Clute. According to Clute’s SF Encyclopedia entry [link] M. K. Joseph was a UK-born resident of New Zealand where he worked as a professor of English and writer. His early novels and poetry were not SF—The Hole in the Zero (1967) is his first, and one of his only, SF works.

Brief Plot Summary/Analysis (*as always, some spoilers*)

The Hole in the Zero is primarily a character driven novel that takes a space opera premise, with (initially) very standard space opera characters, and contorts and manipulates them as the novel progresses. In the first part of the novel three characters (Kraag, Bill, and Helena) arrive on a specially designed spaceship at a small planetoid—run by Seth Paradine—literally at the edge of space: “the Universe ends here. It’s the end of space. What lies beyond it is unspace, untime, unlaw, unpossibility” (12). After a disaster exploring unspace they experience the effects of this different kind of existence.

Seth Paradine—a Limitary Warden, is in charge of a small station on a planetoid on the furthest reaches of space. The expanse, however it might be described, of non-space exists beyond the furthest reaches. His job is watch for incursions from this other realm of existence. In the past incursions of unspace “took out three whole galaxies” (14). His sanity is preserved via an artificial environment which he has programed robots as butlers and maids, the rooms are evocative of English nobility: “When you live on the edge of it, when you look out at it, when you go out into it, you need something. You need something solid, familiar—kind. You need identity insurance” (11). Seth is the most grounded character. He is desperate to find order in disorder, even the disorder of unspace which is not governed by the Universe’s laws. He believes unspace can be understood.

Kraag is the megalomaniac robber baron, people are simply pawns that are manipulated to generate revenue. He has an antagonistic relationship with Bill, despite handpicking him to marry his daughter: “But I warn you, Billy boy, I warn you. I made you out of nothing to be my heir and my daughter’s husband. I gave you whatever you’ve got, and I can take it away again—all of it—credits, exclusive sports-clubs, dollies, space runabouts—the boxful. Even your hand-embroidered clothes. Even your face” (23).

Helena Kraag is the neurotic daughter of Kraag–the embodiment of upperclass ennui and filled with lack of purpose. Like Merganser, she is profoundly troubled by her relationship with her father and her position in society: “‘Mould,’ said Helena, ‘blight, vermin, fungus. We’re eating the universe alive. Nothing but stinking people everywhere. What happens when we run out of universe?” (22).

Hyperion “Billy” Merganser—Kraag’s heir-executive and future husband to Helena. An albino groomed from crude beginnings by Kraag to take over his vast empire and marry his daughter, despite how much he owes Kraag he is filled with incredible resentment that none of what he achieved was due to his own merit. He even owes his name to Kraag. He wallows in empty self-aggrandizement, placates himself with alcohol, and pseudo-philosophical generalizations: “‘Love,’ he said. ‘Nothing. I love nothing” (16).

Before the disaster plunges them into unspace, M. K. Joseph carefully establishes each character’s backstory, relationship with each other, and general philosophies on the world. And then at the end of chapter 2 the shift occurs: as they fall into unspace Seth’s pilot robot transforms in one of the more bizarre images of the novel:

“As it leapt and ran, its body stretched taller and tall, an attenuated metal spider kilometres high, until there was nothing left but the giant head which melted, raining tears of white-hot metal through the void. The ship tilted suddenly, and without a sound Boss Kraag and Billy boy, Miss Helena, and the Warden spilled out” (36).

What follows is an often oblique and obtuse series of character, environmental, and situational permutations—that verge on allegorical—that reinterpret the relationships between the characters. First we move individually through the characters. Billy lives as a member of the Free Cavalry that live out their existence on the backs of strange birds. Kraag, a strange alien presence that consumes rocks and moves among the alien world in search of a mate. Paradine dispenses clean blankets to soldiers in some unknown war. He lives in a warehouse of blankets that create cathedral high spaces of fluffy white. Helana, a dendroid like being, dreads the approach of machine creatures that chews through her rooted compatriots.

Chapter 4 is perhaps the most fantastic chapter of the entire novel. It takes the form of a hallucinatory sequence—the conceptual core of the novel—where one version of Seth Paradine becomes aware that other versions of himself exist in parallel universe (many-worlds interpretation). Fragments of their existence seeps into his existence. Every action yields numerous other versions of himself.

It is hard to describe the narrative of the rest of novel as the constantly bifurcating worlds collapses and the “entire matrix” becomes “rigidly monolinear” (73). Each character attempts to order their own existence, and, it appears that they have, at least in some cases, the ability to consciously manipulate future permutations of their existence. The remaining novel takes the form of short narrative fragments that often pit the order-seeking Paradine against the order-hating Kraag.

Final Thoughts

At the conceptual level The Hole in the Zero will undoubtedly intrigue and simultaneously bewilder. The cast, initially more caricatures than characters, are firmly established in a traditional Space Opera paradigm before much more complex relationship (s) between them are explored in various permutations of being via a series of constantly bifurcating narratives and probabilities. Although John Clute argues that Joseph’s vision is “a significant contribution to the field” my appraisal is more muted. I feel like I need to reread the novel to understand Joseph’s aims and literary allusions. At this point, I would suggest that Effinger’s entropic explorations in What Entropy Means to Me (1972) are more tangible and poignant.

Unlike the vast majority of SF, in The Hole in the Zero Joseph uses high concepts such as many worlds theory as a vehicle to explore character. This is by far the most appealing element of the work. As an often poignant thought experiment I was convinced of its merit. As a work of engaging literature I cannot, at least not yet, agree with John Clute’s fierce endorsement. Regardless, the work deserves a greater readership. I tentatively recommend The Hole in the Zero for fans of New Wave and character driven science fiction.

For more book reviews consult the INDEX

(Uncredited cover for the 1968 edition)

(Frits Stoepman’s cover for the 1974 Dutch edition)

A shame it wasn’t quite up to snuff. But—that Soyka cover! Really dig it.

I don’t really know what to make of the book. I think it needs a reread before I can give it a more firm rating…

Did a quick Google and found this post, which includes an old review from a NZ literary journal.

Yeah, I read that as well. I simply do not have the knowledge of contemporary lit to get at the allusions….

I love the title! But I have to say – after reading your review, I don’t think it’s my cup of tea… Happy New Year to you!

Yeah, it’s a strange book. But, I found it worth the read.

Something really tickles me about books such as this, where the author is well-versed in science fiction but somehow comes from a little outside its normal traditions. It produces books that are familiar but deeply weird and in ways that a pure outsider can’t quite manage right.

After I read your review I poked about online a little and ordered a copy!

Just got it through the post – a 1967 1st UK edition Victor Gollancz h/c in not bad condition, considering it’s age.

Not one of the covers you’ve used here – it’s mauve/purple with a white typeface and an indistinct whirlpool/vortex illustration. It’ll appear on my Flickr photostream once I start it, whenever that may be!

Did you end up reading the book?

Yes, I did. Really enjoyed it.

It was a mind trip for sure!

Sorry, didn’t realise the link would reproduce my Flickr pic of the cover!

Click through it for what I said.

No worries! I did. Seems even more positive than my assessment 🙂

(I have to admit, I mostly forgot the book soon after I read it. It certainly was a kaleidoscope of a read. I did not have a clear picture of it in my memory).